Category Archives: Uncategorized

Enhanced workers’ rights in jeopardy

Filed under Uncategorized

Firefighters’ agreement highlights pay inequalities across public sector

I very much welcome the agreement reached between the Dept of the Environment, Community and Local Government, the Dept of Public Expenditure and Reform and SIPTU to unwind previous allowance cuts for new entrants into a new incremental pay scale for all firefights (3rd May). This new pay scale will equalise the pay of all firefighters – including new entrants who lost a rent allowance of €4,500.

The agreement was reached within the confines of the Landsowne Road Agreement and highlights the issue of pay discrimination across the public service. For example young teachers who entered teaching before 2011 work for up to 20% less than their older counterparts – having lost allowances and suffered a pay cut. This inequality dominated the recent annual teachers conferences where motions to reverse pay inequalities were passed. Nurses are also heavily hit by similar cuts and evidenced by their reluctance to return to Ireland to fill hospital vacancies. Similarly new entrant Gardai have lost allowances currently paid to their longer serving colleagues resulting a two-tier salary scale.

The fire-fighters’ new pay scale that is inclusive of allowances may set a precedence going forward for the resolution of other cases of public sector pay inequality.

Young teachers highlighting pay inequality at 2016 INTO Annual Congress

Filed under Uncategorized

Community Law and Mediation Centre Funding

Funding is always an issue for local community services. News from The Tánaiste and Minister for Social Protection, Joan Burton T.D. yesterday (Thursday 7th April) that Community Law and Mediation is to receive funding of €350,000 from the Department of Social Protection is very much welcome. This funding will support Northside’s Community Law and Mediation Centre’s important local work in the development and promotion of information and welfare rights.

Community Law and Mediation, formerly Coolock Community Law Centre, is a non-profit, independent, community-based organisation that has served the Northside communities for over 40 years. It provides free legal advice clinics every week, mediation services, conflict coaching and information sessions on a wide variety of rights based issues including employment rights and housing rights. It recently partnered with Coolock Library and Near FM to provide a very enjoyable and informative series of free public lectures on the Women of 1916.

I regularly refer constituents to the Centre on a wide range of issues including family, employment, and debt difficulties. Community Law and Mediation provide a vital role removing financial and geographical barriers to accessing professional information, advice and support.

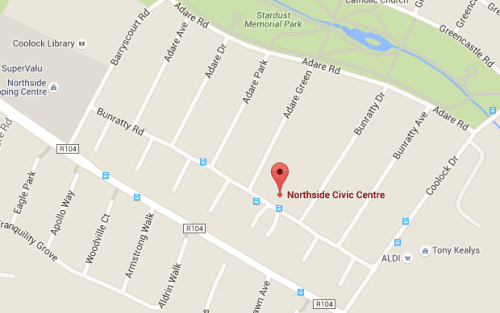

Community Law and Mediation is located in the Northside Civic Centre on Bunratty Rd., Coolock, Tel 01/ 848 2988

Filed under Uncategorized

Good news for Greendale Court Residents

I’m delighted to learn today that funding has been secured from Minister Alan Kelly and the Department of the Environment and Local Government to refurbish the second block of the Greendale Court Senior Citizen’s Complex, Kilbarrack. The conversion of bedsits into one bed units in the first block in this complex is almost compete with residents moving in next month – 32 bedsits have been converted onto 16 one-bed units. The remaining block consists of 31 bedsits and this will deliver 15 one-bed units.

Concerns arose when it came to allocating residents to the newly refurbished block, all the residents wanted to stay together in their supported community – the only way to accommodate everyone was to have both blocks refurbished. Dublin City Council wrote to Minister Alan Kelly some months ago seeking release of funding for the project and I followed up with him last week. Refurbishing both blocks will allow all residents to retain their community spirit and enjoy a more dignified and spacious living space.

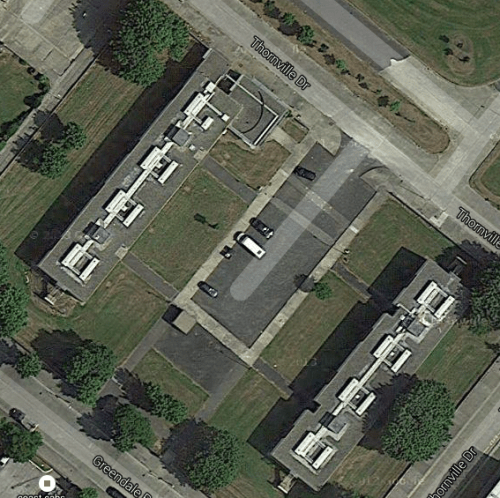

Aerial view of Greendale Court – the refurbishment of the block on the right is almost complete, funding has now been secured for the refurbishment of the block on the left

Filed under Uncategorized

Why vote No 1 Ged Nash in #Seanad16

As those who regularly read my blog know, a core focus of my political and working life is workers’ rights and workplace conditions. Since the last election life has got better for many of these workers thanks to the Labour Party in government and in particular the work of the previous Minister of State for Business & Employment at the Department of Jobs, Enterprise and Innovation, Ged Nash.

During his short tenure Ged achieved significant changes for workers:

- he brought the concept of the living wage to the fore and made it realisable in the future by legislating for a Low Pay Commission that must recommend wage levels to government. This immediately resulted in a second increase in the minimum wage.

- he, against global trends and indeed high court challenges, introduced collective bargaining legislation that provides a strong base to enhance workers’ collective rights to union representation in Ireland

- he amended the Credit Guarantee Bill and overhauled Microfinance Ireland to make it easier to lend money to micro enterprises

- he immediately drew up a report on the the overnight closure of Clerys department store with the loss of almost 500 jobs and then pro-actively commissioned a report into the various legalities that ‘allowed’ the closure happen. This report just released recommends changes in legislation to make this approach to company take-overs illegal

Ged meeting Clerys’ workers vis TheJournal.ie

What is significant in these achievements is how he navigated the political divide between himself and his Fine Gael counterpart Mins Richard Bruton. The difference in ideology between the two parties when it comes to workers’ rights is highlighted in each party’s response to the Irish Congress of Trade Unions’ Charter for Fair Conditions at Work , which contains a commitment to collective bargaining and the living wage. Without hesitation, all Labour Party deputies signed while only 7 FG deputies did. Yet, despite this and despite the fact that the Labour Party was in a 1:2minority, Ged was successful in advancing workers’ rights.

Seanad Labour Panel

Like many other workers and trade unionists, I was deeply upset when Ged lost his seat in the recent election. I couldn’t believe that his pro workers’ rights voice would not be present in the next Dáil. However, his nomination by ICTU onto the Labour Panel of the Seanad gives me great hope that his strong representative voice will be present.

Therefore, if you are a current TD, outgoing Senator, City or County Councillors (or indeed you know one) and you want a pro-active, determined and challenging Senator committed to enhancing and progressing workers’ rights you need to vote No 1 for Ged Nash on the Labour Panel in the current #Seanad16 elections.

Other Labour Candidates in #Seanad16

Other Labour candidates with a similar calibre to Ged’s that I would also ask you to consider are:

- Aodhán Ó’Ríordáin on the Industrial and Commercial Panel

- Kevin Humphries on the Administrative Panel

- Denis Landy on the Agriculture

- Ivana Bacik on the Trinity Panel

- Aideen Hayden and Luke Field on the NUI Panel

Filed under Uncategorized

Thoughts on the eve of #GE16

Tomorrow we go to the polls and vote but what actually does that mean? What’s the bigger picture?

Tomorrow each vote cast will collectively decide who will end up directing policy and legislating for almost every aspect of our lives – how much or how little tax we pay, to what extent our public and community services are resourced and supported or indeed privatised, whether workers’ rights are enhanced and protected or whether the free market is allowed dictate their terms and conditions, whether or not women will be granted autonomy over their own bodies and the right to choose, whether or not access to our schools will depend on having a baptismal certificate.

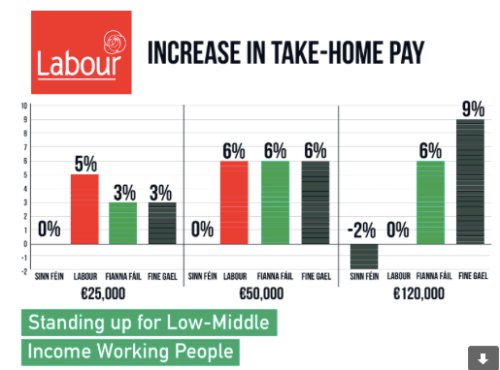

How Labour would like to decrease/increase tax

That is what those elected to the Dáil explicitly do – they legislate. However, more implicitly they set an example for the country – their attitudes set a tone and their values and behaviour set the subtle parameters for what’s deemed right and wrong.

Tomorrow, without hesitation, I’m voting NO 1 Labour and here’s why

Labour entered government with Fine Gael, a party at the opposite end of the political spectrum to us, 5 years ago when our country was on its knees and had no control over the decisions that were made for us, its citizens.

Why were we on our knees?

Because, on the verge of bankruptcy, we had to be bailed out, repossessed by the TROIKA in November 2010. They loaned us the money we needed to may our state bills – to pay our nurses, our Gardai, our teachers – to keep the country going. They aid down the rules and conditions of that bank loan. Sadly, this point has been lost in much of the #GE16 debate, particularly when it comes to the myth and accusations that Labour broke its promises – but more on that shorty.

Why did we enter government? Simply because we cared for and about our country and our citizens. Fine Gael’s election manifesto sought massive public expenditure cuts (public services and welfare) compared to tax increases (Labour sought the reverse) and we knew that those who needed and depended on these services most would be hardest hit – we couldn’t stand idly by and shout from the sidelines when we were in a position to do something constructive about it.

A 5 year coalition

And so the 5 year battle as a minority government party to put decency, rights and responsibility at the heart of legislation and national policy began. We did not succeed on every level with our coalition partners. Probably, the best/worst example is the benchmarking of rent increases to inflation – we wanted that, Alan Kelly and colleagues fought for that but we lost, Fine Gael wasn’t having it (or either there was nothing left to barter). We lost also on certain cuts to welfare allowances and thresholds. No doubt our detractors can list lots more.

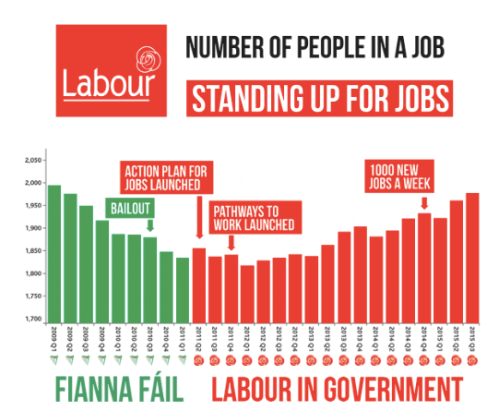

We won, however, on enhancing workers’ rights – globally unions are being isolated and decimated and we, with Minister Ged Nash to the fore, legislated for collective bargaining rights; we increased the minimum wage twice and legislated for a commission to monitor it. We won on increasing USC for higher paid workers – a new band for those earning €70k was introduced in Budget 2015. We won on securing the partial unwinding of the FEMPI legislation through the Landsdown Road Agreement. We won on greater investment in social housing. We won on securing (and winning) a referendum on the right to marriage regardless of sexual orientation. We won on job creation – over 120,000 new jobs, new starts for those that were unemployed. We won on maintaining a threshold of decency while we brought our country back from the brink, while we regained our sovereignty, eventually in December 2013, and with it our right to decide investment and expenditure for ourselves.

The future

It’s unfortunate that the slogan ‘a lot done, more to do’ has been sullied but a lot has been done and Labour has been to the fore in much of that. There is a lot more to do and Labour want to continue on where we left off. Good politics is about negotiating and compromising to get things done even though it’s only partly the way you’d like them to be done. Good politics is not black and white, not absolutist, not my way or the high way. Good politics is caring enough about the country to work with what you’ve got, including sacrificing a little of your own self, to make things better for everyone and pave the way for a better future.

Our country is in a much better place than it was 5 years ago. Labour has played a big part of making it a better place, a more equal and a fairer place. It’s still a long way off how we’d like it but the only way to get it nearer to a more equal society underpinned by a strong economy with decent jobs it is to vote for us – vote No 1 for your local Labour candidate tomorrow. Vote for a party that is willing to work for a better, fairer future for you and those coming after you.

Vote No 1

Filed under Uncategorized

Fair Conditions at Work

At my first meeting of the Council I proposed an emergency motion to support the Greyhound Workers in their locked-out work situation. Since then I have raised concerns about Dublin City Fire Brigade staffing levels and their health and safety in the absence of proper a risk assessment audit of the city, have spoken to a motion condemning the appalling treatment of the Clery’s Workers – I urged DCC to protects the use of the Clery’s building for retail in the Special Planning Control Scheme for O’Connell St. My most recent advocation for workers’ rights was bringing a motion seeking that DCC support the Irish Congress of Trade Union’s Charter for Fair Conditions at Work in November 2015.

This Charter sets out five key principles that constitute fair conditions:

- A Living Wage – a wage that affords an individual sufficient income to achieve an agreed, acceptable minimum standard of living

- Fair Hours of Work – the right to a regular contract of employment which provides security of hours and certainty of income

- The Right to Representation & Collective Bargaining – the right to be represented without fear of victimisation and to have a union represent them in collective bargaining negotiations with their employer.

- Respect, Equality & Ethics at Work – the entitlement to be treated with respect and dignity, as they go about their work without being subjected to discrimination, harassment

- Fair Public Procurement – that worker employed under a publicly-tendered contract is entitled to enjoy all the rights and protections outlined in this Charter

My motion focused particularly on the Fair Public Procurement aspect of the Charter. This aspect of the motion/Charter is dictated by three new EU Directives which must be passed into Irish law by April this year. How these Directives are legislated for will have a impact on workers working for companies that secure public procurement contracts – potentially their rights and entitlements can be significantly protected.

To support my DCC Councillor colleagues’ understanding of the Charter and to encourage them to sign up to it, I invited ICTU General Secretary to give them a briefing on the details. I’d like to support all those attended, signed the Charter and supported my motion. Dublin City Council’s support for Fair Conditions at Work is an important statement for those who work for our local authority either by direct or indirect contracts.

Below is my press statement on the passing of the motion

“Dublin City Council is the largest council in the country and not only is it a significant employer but also awards a significant number of public contracts so the acceptance of the 5 principles of the Congress Charter will impact positively on a vast number of workers”

“Paying a living wage; providing fair working hours; the right to union representation and collective bargaining; respect, equality and ethics at work and fair public procurement are the five elements of the Charter.”

“Dublin City Council fully recognises trade unions – their employees are represented by IMPACT and SIPTU and their terms and conditions are determined in the main under collective bargaining agreements. However, when it comes to public procurement and the outsourcing of contracts there is no guarantee that, in practice, the terms and conditions of contracted workers comply with labour law or labour agreements particularly when it comes to subcontracted workers — fair public procurement procedures will ensure this”

“Fair procurement processes also allow for the weighting of social considerations so that contracts are both economically advantageous to the local communities and contractors. They also allow for the consideration of a contractor’s history with regard to compliance of legal sand employment rights and obligations thus legitimately affording the exclusion of employers that regularly do not uphold or respect employee rights and entitlements”

“I recognise that the passing of this motion is only a stepping stone in ensuring Dublin City Council applies the principles of fair procurement. We will need to ensure that appropriate resources are put in place to ensure the maximising the potential of fair procurement process in favour of workers and of local communities, particularly in the area of compliance with contract details”

Text of Motion

The Congress Charter for Fair Conditions at Work seeks a societal consensus as to what constitutes fair conditions of employment. The charter identifies five key principles which, as a minimum, should be respected by every employer: a living wage, fair hours of work, the right to representation and collective bargaining, to be treated with dignity when at work and fair public procurement. This council supports and advocates the implementation of the Congress Charter for Fair Conditions at Work for all DCC employees and applies its principles in it public procurement process. In particular, DCC will:

- work with DCC employees’ union representatives to ensure the implementation of the Charter across all DCC departments/sections

- apply the following principles of public procurement as per EU Public Procurement Directives:

• Most economically advantageous tender (M.E.A.T.) so formulated to always include social considerations such as the impact on local employment. Under this DIRECTIVE it is essential that social considerations are given a suitable weighting.

• Compliance with Labour Law: ‘Member States shall take appropriate measures to ensure that in the performance of public contracts economic operators comply with applicable obligations in the fields of environmental, social and labour law established by Union law, national law, collective agreements or by the international environmental, social and labour law provisions’ Article 18

• Inclusion of Social Clauses: to detail specific criteria to require as a condition of the contract, respect for employment rights, including respect for right to collective bargaining and compliance with relevant JLCs (and EROs/REOs and REAs) and/or relevant Minimum/Living Wages (ILO Convention 94 on Labour Clauses in Public Contracts).

• Selection and Exclusion Grounds for Tendering: including the exclusion of abnormally low tenders, having regard for economic and financial standing of tenders and previous behaviour compliance behaviour with legal/employment rights obligations

• Joint and Several Liability in Contracting Chains: that the tenderer be asked to indicate in its tender any share of the contract it may intend to subcontract to third parties and to name and have oversight of any proposed subcontractors.

Filed under Uncategorized

The Teachers’ Voice

This is the copy of the book chapter I co-wrote with Prof Howard Stevenson of the University of Nottingham. The chapter, The Teachers’ Voice: Teacher Unions at the Heart of A New Democratic Professionalism, was written for a project called ‘Flip the System‘ – an initiative by two teachers from the Netherlands, Rene Kneyber and Jelmer Evers, to bring an alternative view from the ground to the debate on education reform. The book was published earlier this year.

Introduction

Teachers across the world are under pressure. It seems that everywhere the demands on teachers are increasing whilst at best the growth of resources fails to keep pace. In very many parts of the world, and especially following the global economic crisis, resources devoted to education are diminishing. The pressure is on to get ‘more for less’ from public education systems, and those who work in them.

Teachers experience these developments in myriad ways, but perhaps most sharply in the form of labour intensification – put simply, the relentless drive to work teachers harder and harder, sometimes until they simply burnout. Many school systems now operate on a high turnover-low cost model of teaching which cycles through an endless process of ‘bring in-burnout-replace’. However a parallel but arguably more significant development is the drive to assert ever greater control over the content of teachers’ work – what teachers do, how they do it and teachers’ ability to decide for themselves what is the most appropriate way to perform their job. Hence the trend to scrutinise teachers’ work forensically, and to convert key elements of the educational process to a number that can be easily measured, compared and ranked. Where this is happening teachers experience their work as being stripped of its pedagogical richness and complexity, to be a replaced by a process of management by numbers.

In this chapter we set out to show how teachers can reclaim their teaching. We do so by making the case for a new democratic professionalism based on the fundamental values of social justice and democracy and with teachers’ professional agency at its core. In the chapter we identify three domains of professional agency as areas of teachers’ work where it is vital that teachers are able to make and shape important decisions. However, our view is that teachers must understand their agency as both individual and collective and we argue that if teachers are to genuinely ‘flip the system’ then this can only be achieved if teachers organise collectively. Teacher unions therefore, as the independent and democratic organisations that represent teachers’ collective voice, are not only at the heart of a new democratic professionalism, but must be central to both making the case for it and mobilising teachers to achieve it. We conclude the chapter by setting out the steps that unions must themselves consider in order to mobilise teachers around a much more optimistic and hopeful vision of teaching.

Teacher professionalism and teachers’ voice

The concept of professionalism has always been problematic when applied to teachers as an occupational group. Traditional notions of professionalism were grounded in identifying the traits associated with ‘classic professions’, such as law and medicine. They emphasised a professional knowledge base and associated levels of expertise, professional autonomy, a commitment to public service and professional self-regulation. In most jurisdictions these are not characteristics that can be readily applied to teachers. There is little evidence of consensus about the role and status of pedagogical knowledge as it applies to the practices of teachers, whilst notions of professional autonomy have always been complex. Finally, professional self-regulation has seldom existed in the ways in which it is evident in many other professions. For these reasons, teaching has often been identified as a ‘semi-profession’ (Etzioni, 1969).

Given these debates some have suggested the concept of professionalism when applied to teachers is ‘beset with conceptual difficulties and ambiguities’ (McCulloch et al., 2000, p14) to the point that they question whether it has any meaningful intellectual value. Whilst we have sympathy with such an approach we also argue that notions of teacher professionalism cannot be ignored because conceptions of ‘professionalism’ cannot be disconnected from much wider questions about how society perceives teaching, and what it means to be a ‘good teacher’. Notions of the ‘good teacher’ are not fixed (Connell, 2009) and are in turn bound up with the on-going discourse and disputes about the nature and purposes of education. This approach was recognised by Ozga and Lawn (1981) when they argued that the concept of professionalism, and the struggles over its meaning, are best understood as a construct mobilised by competing groups in society to legitimate different, and oftentimes quite contradictory, approaches to teaching as work. Hence the state might refer to teacher professionalism in terms of responsibility and respect (the teacher as ‘model citizen’), whilst teachers might emphasise a professionalism based on expertise and pedagogical knowledge in order to make the case for greater autonomy.

This struggle over the meaning of professionalism is at the heart of many of the current debates about teaching and the role of teachers. Neoliberal education reformers have always been deeply sceptical of the concept of professionalism, seeing it as a device used by ‘producers’ to protect the vested interests of the ‘education establishment’ at the expense of ‘consumers’ (Demaine, 1993). This anti-professionalism is particularly critical of producer interest groups in education (such as teacher unions and educational researchers) because of the powerful ideological role that education performs in society. The ‘educational establishment’ not only protects its own vested interests, but it is also responsible for promoting a dangerous egalitarianism in schooling. Hence the argument that such producer interests must be curbed, in particular when organised in the form of unions, and that this is most effectively achieved by introducing the ‘discipline’ of market forces into public services. Many have argued that it is these pressures that have driven a form of ‘managerial professionalism’ (Whitty, 2008) whereby teachers’ professionalism is recast in terms of an ability to achieve specified performance targets in a competitive (quasi-) market environment (Stevenson et al., 2007).

For many years these ideas have been challenged by those who have made a case for a more optimistic and hopeful vision of professionalism and in this chapter we draw on three of these sources in particular. Firstly we are indebted to Judyth Sachs (2003) and her work relating to ‘The activist teaching profession’. Sachs’ book made a major contribution to thinking about teacher professionalism in new and more optimistic ways, but perhaps in particular it emphasised that professionalism must be both collective and active. Professionalism is more than passive membership of a club, but teachers must be active in creating and re-creating their collective professional identities. We also draw on Geoff Whitty’s (2008) case for ‘democratic professionalism’ in which he emphasises the need for teachers to work ‘beyond the profession’ in order to draw broader constituencies into the educational process. According to Whitty such a democratic professionalism

‘ . . . seeks to demystify professional work and forge alliances between teachers and excluded constituencies of students, parents and members of the wider community with a view to building a more democratic education system and ultimately a more open society.’ (p44)

Finally, in emphasising the importance of teacher agency in relation to a new democratic professionalism we very much draw on ideas presented by John Bangs and David Frost (2012) in their work for Education International.

Teachers’ voice and teacher unions

Ambiguities relating to the nature of teacher professionalism as a concept are also evident in relation to the role and purpose of teachers’ unions as the organisations that articulate teachers’ collective and professional voice. The use of the term ‘union’ clearly associates such organisations with the labour movement, and the notion of the teacher as a worker. This is an important statement of an objective position. The vast majority of teachers are employees, in an employment relationship in which their labour power (the ability to work) is traded in an exchange relationship with an employer (whether that is in the public or the private sector). Teaching is work and teacher unions therefore might rightly be expected to have a clear role in relation to defending and extending the pay and working conditions of their members. However, within the teaching profession, the role of teacher unions has always been much more complex with unions often claiming to be both labour union and professional association. Teacher unions therefore represent teachers’ collective voice across a very broad range of issues.

Our argument is that the ‘industrial vs professional’ debate within teacher unionism will always be an underlying tension that can never be completely resolved, but that to frame discourses about teacher unions solely in these terms is unhelpful and unproductive. The issues facing teachers, and the contexts in which teachers teach will always be determined by a mix of so-called professional, industrial and policy issues. For example, a policy to reduce class sizes has both a pedagogical dimension (professional) and a workload implication (industrial). Similarly, we believe it is not possible to challenge the spread of the managerialism that blights many teachers’ lives without having a wider political analysis of the global education reform movement (GERM) that has spawned it and drives it. Questions of politics and professionalism can never be artificially separated from more fundamental questions about the role of teacher unions in protecting basic pay and conditions.

Our view is these diverse issues need to be fused together to define a new vision of a democratic professionalism and that teacher unions have a central role in both articulating what this might look like, and crucially, mobilising teacher support to campaign for it. At one level teacher unions are at the heart of teacher professionalism because of their ability to represent the collective voice of teachers. However, teacher unions also represent the means by which a new democratic professionalism can be achieved. A new democratic professionalism will always need to be argued for, (re-)defined and fought for. Mobilising teachers around these aims will be a key challenge for teacher unions as they resist the spread of the GERM.

In the following section we develop our ideas about what a new democratic professionalism might look like and subsequent to this we set out the role of teachers’ unions in mobilising teachers in pursuit of these aims.

Re-asserting teachers’ voice: making the case for a new democratic professionalism

Underpinning our argument in this chapter, and the analysis in this book, is that there is currently a global struggle for the heart of education as a publicly provided democratic service. Inevitably this looks different around the world, but the threat has assumed the form of a global movement, and hence the response must be similarly global in form. Our conviction is that teachers must challenge the managerial view of professionalism that underscores the global education reform movement, and in its place articulate a much more optimistic vision of what education can look like, and what it means to be a teacher. Here we outline a framework that might underpin a new democratic professionalism, and in the final section we set out the organising strategies that teachers, working through their unions, will need to adopt in order make the prospect of a democratic professionalism a genuine possibility.

Our vision of a new democratic professionalism is based on three core principles:

- That teaching is a process of social transformation and that it should be underpinned, above all else, by values of social justice and democracy.

- That teaching is a technically complex process in which teachers need to draw on professional knowledge, pedagogical theory and personal experience in order to exercise professional judgement. Professional judgement requires agency by which teachers are able to make meaningful decisions based on assessments of context. The concept of teachers’ professional agency must be at the heart of a democratic professionalism.

- That teachers’ professional agency must be considered as both individual and collective. At times teachers will be able to assert their agency as individuals, quite appropriately. However, in order to secure meaningful influence in relation to the fundamental elements of teachers’ working lives then teachers will need to assert their influence collectively.

We are clear that any vision of a new democratic professionalism must be grounded in values that recognise the role and responsibility of public education, and hence the role and responsibilities of those who work as educators. Clearly there will be a wide range of views about what those values should be, and how these might be expressed. However, our view is that education is a public good and therefore the core values informing the service should reflect a commitment to social justice and democracy. If education is a citizenship entitlement then it must be underpinned by a commitment to equality. Similarly a commitment to democracy recognises the central role education plays creating an active, participatory citizenship. It also recognises that if schools have a role in preparing young people to be active citizens in a democracy, then schools themselves must be models of democratic practice.

In addition to this we argue that democratic professionalism is underpinned by a strong sense of teacher agency (Bangs and Frost, 2012) whereby teachers can exercise meaningful levels of control and influence in relation to three key areas of their work – we identify these as domains of professional agency.

The first domain of professional agency is in relation to teachers’ ability to shape learning and working conditions. Learning and working conditions can be considered to include all those factors that frame the environment within which teachers’ work, and in which students’ learn (Bascia and Rottmann, 2011). Such a list of factors is inevitably very broad. It would include issues such as the size of the class, the way classes are formed, the use of technology to support learning, the amount of preparation time a teacher receives and pay and reward determination. These are all aspects of teachers’ working lives in which a democratic professionalism would ensure that teachers were involved in meaningful decision-making. The precise form of this will inevitably vary but could include a range of possibilities from the freedom of teachers to make individual decisions in their own classroom through to national collective bargaining processes. The list of issues presented here also reinforces the unhelpful divisiveness that flows from distinguishing between so-called ‘industrial’ and ‘professional’ issues and instead recognises that all these factors have the ability to shape the learning experience.

The second domain of professional agency pertains to the development and enactment of policy. In this context we identify policy as the operational statements of values that frame the contexts in within which teachers’ work. Policy is often perceived as the preserve of upper case ‘P’ politicians, and ‘what governments do’. This is clearly a decisive factor in framing the contexts of teachers’ work, however, our notion of democratic professionalism sees teacher agency in relation to policy operating at many different levels with institutional policy making having a very significant impact on teachers and their work. Meaningful teacher agency in relation to the development and enactment of policy would ensure that teachers’ voices were heard not only in relation to national issues, such as the development of national curricula, but also, crucially, at school level also.

The third domain of professional agency we identify relates to teachers’ ability to develop their professional knowledge and professional learning, and teachers’ agency in this regard emphasises the ability of teachers to assert control over their own professional development. One feature of a managerial professionalism relates to the ways in which teachers’ professional knowledge has often been ignored as particular pedagogical practices have been imposed on teachers, whilst in other cases professional development has been used crudely to promote national initiatives or organisational objectives. These initiatives are often geared to meeting externally imposed targets, rather than being driven by the professional needs of the teacher. In a democratic professionalism teachers could expect to assert much more control over their own professional development, with correspondingly lower levels of imposition. In our view such professional development is likely to be both research-informed and research-engaged, with teachers actively involved in building the profession’s knowledge base.

We argue therefore that a democratic professionalism, based on fundamental values of social justice and democracy, emphasises teacher control and influence in relation to three domains of professional agency – shaping learning and teaching conditions, developing and enacting policy and enhancing pedagogical knowledge and professional learning. In making this case we also assert the need to consider agency as working at many different levels – from the individual classroom, through intermediate tiers (the school, local or regional government) to national government, and indeed to supra-national institutions. However, in order for agency to be exercised in these diverse environments it is vital that agency is understood as both individual and collective.

Many aspects of teacher agency that we have referred to should quite appropriately be a matter for individual teachers. A feature of any form of professionalism should be the scope for individual autonomy, and for those with high levels of skill and expertise to be able to exercise professional judgement without the need for micro-management from above. However, in relation to many of the issues raised in this chapter, agency cannot be exercised at the level of the individual alone. This may reasonably be applied to the level of government, where the capacity of individuals to make a difference is understandably limited. However, such an argument can be applied elsewhere in the system, when we recognise that there are many occasions when teachers must organise collectively if they are to be able to assert their influence. This is why teachers’ unions are at the heart of a democratic professionalism. Partly, and most obviously, because they promote collective agency by combining together and asserting the amplified voice of organised teachers. However teacher unions also have a central role to play in challenging managerialism more generally and thereby creating the spaces in which teachers can exercise their individual agency.

In this analysis teacher unions are central to the development of a new democratic professionalism. However if teacher unions are to be successful in setting this agenda they will need to work differently in order to draw a broader range of members into participation in the union. As such mobilising for a new democratic professionalism both requires union to renew themselves, but also offers the possibility of creating the conditions for renewal itself.

Renewing teacher unionism: organising for a new democratic professionalism

We have argued thus far that public education systems globally face a major threat, and that teacher unions represent a powerful bulwark against the attacks of the global education reform movement. However, teacher unions cannot afford to only be defensive in the face of this threat, but rather they need to assert a much more hopeful and optimistic vision of what it means to be a teacher. In this chapter we have sought to map out the broad features of what a new democratic professionalism might look like. Our argument is that this cannot be a vision that unions articulate for teachers, or on behalf of teachers – but that teachers must see themselves as integral to the union. This is the essence of collective agency and the notion of an activist professionalism (Sachs, 2003).

Our argument is that if teacher unions are to successfully articulate a new democratic professionalism then this must form part of a wider process of renewal in which the unions themselves develop as active, vibrant and engaging organisations. In summary, teacher unions as organisations must become models of the new democratic professionalism they seek to promote. In practical terms this involves the development of an organising culture in teacher unionism. We believe such an organising culture is predicated on three different elements:

Organising ideas – we have already argued that the ‘industrial vs professional’ debate within teacher unionism has been unhelpful. So-called industrial and professional issues cannot be readily separated, and the bifurcation serves to divide. Our view is that teacher unions must develop a much more holistic analysis of the teachers’ role, in which working conditions, professional issues and policy are all linked. This necessarily requires teacher unions to make explicit the political dimensions of policy that are often only implicit. The global education reform movement is a politically driven movement grounded in a globalised neoliberalism. A pedagogical issue such as assessment and testing cannot be separated from the wider questions of the purposes of assessment and testing. Who is driving the demand for more testing? For what purpose? Who gains as a result? These are ideological arguments and they need to be challenged ideologically. This is why teacher unions must not retreat from engaging in ‘professional’ issues, but they must also locate these issues in a much wider political context. Organising around ideas requires teacher unions to engage in the battle of ideas that must be won if the neoliberal dismantling of public education is to be successfully challenged. This is not a battle to be waged amongst the policy elites and disconnected intellectuals, but one in which teachers themselves need to be actively engaged as ‘organisers of ideas’ (Stevenson, 2008), or what Antonio Gramsci (1971) referred to as ‘organic intellectuals’.

Organising from the base – a common feature of labour unionism is a desire to centralise, as this is perceived as an effective means of securing equity. In many contexts, national collective bargaining has been seen as pivotal to securing national pay scales, and therefore a significant measure of pay equity. One consequence of this has been the centralisation of union structures as union organisation mimics the bargaining structures within which unions function. Such structures can have many merits, especially in contexts where national bargaining has been maintained. However, there is always a danger that over time the grassroots membership becomes disconnected and passive. Collective agency is asserted, but in a largely transactional manner. Members pay their subscription and then expect the union to represent them. Teachers are part of the union, but they do not expect, and often are not expected, to be active participants. The danger is that a dependency culture on local ‘hero leaders’ can develop and in the longer-term grassroots organisation atrophies. Organising from the bottom-up directly challenges this approach by ensuring that teachers recognise they are the union. This then requires the active development of the union at its base by engaging members in union activity. This may be quite traditional in form, such as organising around a local grievance, but our argument is that traditional notions of ‘activism’ are no longer sufficient and a much more inclusive approach to ‘activism’ needs to be considered. Participating in union organised professional development for example is an important way in which teachers experience and connect with their union, and through which, for example, the battle of ideas discussed above is advanced.

In summary, we believe that teacher unions need to focus attention on building the base in their organisations. Teachers need to experience their union as a key part of the their identity and ‘live’ the union whether it be through traditional workplace activity, union organised professional development or union sponsored social and cultural initiatives. None of this is easy – it can be costly in resources and requires a long-term perspective. It is however unavoidable if teacher unions are to build a strong organisation capable of halting, and then reversing, the forward march of neoliberalism in public education.

Organising for unity – the term union reminds us that the role of labour unions is to unite the disparate interests of individuals so the fractured power of isolated employees is combined and magnified through collective organisation. Unity is perhaps the most basic principle of trade unionism. It is however a principle that has not always been replicated within teacher trade unionism. For reasons too complicated to elaborate on here it is important to note that in many different jurisdictions teachers as an occupational group have failed to organise into a single union. As a consequence, so-called ‘multi-unionism’ in teaching is a common phenomenon. It can differ in form (different unions organising different groups of teachers for example) but in several instances it includes different unions competing directly against each other for the same teachers. It is difficult to see how this defiance of the basic principle of trade unionism can serve the bests interests of teachers. Our argument is that such divisions are now dangerously complacent in the face of an unprecedented attack on public education systems and the teachers who work in them. A key feature of the market-driven GERM is its intent to break-up and fragment, as a deliberate attempt to undermine the influence of professional interests within public education systems. Teacher unions cannot compound these divisions in the system by being further divided themselves. In order to facilitate renewal it will be important for unions to organise for greater co-operation, working together strategically and tactically but ideally moving towards union mergers.

However, organising for unity cannot be seen as being purely about working for union amalgamations, which always carries the attendant risk of being a largely bureaucratic process. An activist professionalism must also develop unity in much more organic ways within and beyond the teaching profession. For example, teachers as an occupational group, in very many different contexts, are becoming an increasingly diverse profession. Routes into teaching are becoming more diverse, and the teaching workforce can look correspondingly different. In many respects, although not in all, increasing diversity is to be welcomed. There are however dangers that an increasingly heterogenous profession becomes correspondingly more fragmented. The challenge for teacher unions, will be to seek to unify the profession, when very many tendencies push in contrary directions. Organising for unity will require teacher unions to find the common interests between teachers, in a world where employer interests will often be emphasising difference and division.

However, the search for unity cannot be confined to within the profession, but if it is to be successful as a movement for progressive change must extend beyond the profession. By this we mean that an activist democratic professionalism must involve an active engagement with students, parents and the wider community and that organising for unity must seek to develop common interests across diverse groups in the community (Whitty, 2008). We see the forming of such alliances as central to building a broad movement capable of challenging the GERM, and turning the tide against it. Once again, we do not underestimate the difficulties of doing this. Indeed research we have been involved in, has highlighted precisely how difficult this can be to achieve in practice (Stevenson and Gilliland, 2014). Teachers and parents are not always ‘natural allies’ and forging coalitions with community interests is complex and challenging. However, we see the development of popular alliances as not only central to developing the broad movement required for progressive change, but as fundamental to making any claim for democratic professionalism to indeed be genuinely democratic.

Conclusion

Teachers are not simply at the heart of public education – they are its heart. The centrality of teachers, and teacher quality in education systems, is now widely acknowledged (OECD, 2005). However, very different visions of teaching are emerging (Hargreaves and Fullan, 2012). One approach uses the language of teacher quality but at the same time seeks to drive down the costs of teaching and de-skill the work of teachers. It is based on a business model of education that seeks to maximise return on investment.

Teachers need to reclaim their teaching and assert a much more positive and optimistic vision of what teaching is, and what it means to be a teacher. It is not enough for teachers to be against managerialism and centralised imposition (although this can be an important springboard for activism). Teaching is intrinsically a hopeful endeavour and teachers need to be positive in their intent.

We believe this involves mobilising teachers, globally, around a much more positive vision of teaching. In this chapter we set out one element of that as a new democratic professionalism. It is not presented as a model or a blueprint, but rather it offers a framework to think about teaching and the role of teachers. It is necessarily flexible and needs to be the subject of much more discussion and debate.

A new democratic professionalism recognises the complexity of teaching and the sophisticated skills involved in the teaching process. Crucially it highlights the need for teachers to be able to assert their professional voice in relation to all the fundamental elements that frame their work – learning and teaching conditions, pedagogical knowledge and professional development and education policy broadly defined from institutional to national and supra-national level. We identify these elements as the three domains of teacher professional agency. However, in making the case for professional agency we are also arguing that this need to be located in a much deeper vision of a socially just and democratic approach to public education.

Such a vision of a new democratic professionalism goes against the grain of current policy in many parts of the world. It therefore requires teachers to challenge current orthodoxy and ‘flip the system’. Our argument is that this is simply not possible unless teachers recognise the need to act collectively, and organise accordingly. Individual teacher agency is important in a new democratic professionalism, but it is insufficient. Teachers must assert their agency collectively if they are to successfully turn the tide on the progressive tide of competition, marketization and privatisation.

This is why teachers’ unions are central to the new democratic professionalism because they are the means by which collective agency can be asserted. They are by no means the only possibility for collective agency, and nor should they be. However, they are the organisations that provide teachers with a voice that is collective, independent and democratic. These three elements alone make teacher unions fundamental to a new democratic professionalism. However teachers cannot rely on a type of transactional collectivism (‘what is the union doing about . . . ?’) but teachers must recognise that they are the union.

Teachers will not ‘flip the system’ unless, and until, they organise collectively. In this chapter we have attempted to trace out a vision of a new democratic professionalism that teachers can organise around. It is obviously incomplete and imperfect and we invite others to critique and develop the ideas presented here. As such our vision of a new democratic professionalism is not an end in itself – but a means to an end. The ultimate end, which will always be just beyond our reach, is a much more inspiring and transformatory experience of education for young people in public schools. If that is a vision worth fighting for then it is one for which teachers will need to organise collectively to achieve.

References:

Bangs, J. and Frost, D. (2012) Teacher self-efficacy, voice and leadership: towards a policy framework for Education International. Cambridge University/Education International http://download.ei-ie.org/Docs/WebDepot/teacher_self-efficacy_voice_leadership.pdf

Bascia, N., and Rottmann. C. (2011) What’s so important about teachers’ working conditions? The fatal flaw in North American educational reform, Journal of Education Policy 26 (6) 787–802.

Connell, R. (2009) ‘Good teachers on dangerous ground: towards a new view of teacher quality and professionalism’ Critical Studies in Education, 50 (3), 213-229.

Demaine, J. (1993) ‘The new right and the self-managing school’, in J. Smyth (ed) A socially critical view of the self-managing school, London: Falmer.

Etzioni, A. (1969) The semi-professions and their organization, New York, Free Press.

Gramsci, A. (1971) Selections from the Prison Notebooks, London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Hargreaves, A. & Fullan,M. (2012) Professional Capital: Transforming Teaching in Every School. London: Routledge.

McCulloch, G., Helsby, G., & Knight, P. (2000) The politics of professionalism: teachers and the curriculum. London: Continuum.

OECD (2005) Teachers matter: Attracting, developing and retaining effective teachers, Paris, OECD.

Ozga, J., & Lawn, M. (1981). Teachers, professionalism and class: A study of organized teachers. London: Falmer Press.

Sachs, J. (2003) The activist teaching profession. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Stevenson, H. (2008) Challenging the orthodoxy: union learning representatives as organic intellectuals in Journal of In-Service Education, 35 (4) 455-466.

Stevenson, H., Carter, B. and Passy, R. (2007) ‘New professionalism’, workforce remodelling and the restructuring of teachers’ work in International Journal of Leadership for Learning , volume 11 (15) available online at http://iejll.synergiesprairies.ca/iejll/index.php/iejll/issue/view/37 (accessed 1st October 2014).

Stevenson, H. and Gilliland, A. (2014) Natural allies? Understanding teacher-parent alliances as resistance to neoliberal school reform, paper presented at AERA Annual Meeting, Philadelphia, NJ April 3rd-7th.

Whitty, G. (2008) Changing modes of teacher professionalism: traditional, managerial, collaborative and democratic, in B. Cunningham (ed) Exploring professionalism, Bedford Way Papers, London: Institute of Education.

Filed under Uncategorized

Christmas period homeless information & services

IF YOU ARE IN NEED OF EMERGENCY ACCOMMODATION

If for any reason you find yourself without accommodation and you are in need of emergency accommodation over the Christmas period from December 25th 2015 until January 3rd 2016 please contact Dublin City Council’s Homeless FREEPHONE on 1800 707 707. This service will be available everyday from 10am until 2am.

IF YOU ARE A FAMILY AND ARE ACCOMMODATED IN A COMMERCIAL HOTEL

The four Dublin local authorities have been contingency planning since October 2015 to ensure that the placements for households that are currently accommodated in commercial hotels can be extended through the Christmas period into early January 2016, whilst daily local authority placement offices are not open.

Where hotels are closing for the Christmas period, alternative placements have been put in place.

This information has been communicated to all relevant families, however we would appeal again to families to contact 1800 707 707 if they are concerned about their placement.

IF YOU ARE AT RISK OF ROUGH SLEEPING

If you are at risk of rough sleeping, please contact the Housing First Service on 086 813 9015 from 7am until 11am to assist you to access emergency accommodation.

This service is the official on- street response team to assist you if you are at risk of rough sleeping. Please contact the service immediately and be aware that if you are outside the city centre area, transport will be available to bring you to accommodation if you need it.

We would also like to appeal to members of the public to contact the service on www.homelessdublin.ie if they meet a person who is rough sleeping. The website provides a quick link to be completed, that will immediately alert the Housing First Service to the location of the person who might be sleeping rough.

IF YOU ARE RENTING AND WORRIED ABOOUT LOSING YOUR HOME

If you are renting privately and are worried about your lease ending before Christmas or early in the new year, the Dublin local authorities would urge you to contact their dedicated Tenancy Protection Service, provided by Threshold on 1800 454 454 as soon as you feel your tenancy is at risk.

ANNUAL CHRISTMAS DAY DINNER

The Knights of Columbanus continue to host the annual Christmas Day Dinner in the RDS, Ballsbridge, Anglesea Road Entrance. A free bus service is provide to and from the RDS every 20 minutes from 9.30am from three pick up points;

- Mansion House -Dawson Street, Dublin 2

- Four Courts – Inns Quay, Dublin 1

- Clery’s Clock – O’ Connell Street, Dublin 1

DAY SERVICES

There are a range of day services that are available and open throughout the Christmas period including;

- Capuchin Day Centre – 29 Bow Street, Dublin 7

- Merchants Quay Day Service and Night Café – Riverbank, 4 Merchants Quay, Dublin 8

- Focus Ireland Coffee Shop – 15 Eustace Street, Temple Bar, Dublin 2

Filed under Uncategorized

Oscar Traynor Rd. Lands Development

The development of the so called Lawrence Lands on the Oscar Traynor Rd. has long been mooted. Over the last 18 months since their identification as part of DCC’s Land Development Initiative things have begin to move. I continue to argue as to HOW these lands might be developed in a previous blog. This blog focuses on the stated objectives for the land as outlined by DCC in the draft Dublin City Development Plan.

The recent draft Dublin City Development Plan has assigned the lands the status of Strategic Development and Regeneration Area. The draft plan contains a number of objectives for the site. (see page 152 of the draft plan).

Submission

DCC sought public submissions on any aspect of the draft development plan. The details below constitute my submission on SDRA 17 for lands on the Oscar Traynor Rd.

Development on this site is most welcome particularly given the current housing supply crisis. A high quality well designed and considered development on this site has the potential to draw together several smaller local areas that lack key social amenities: Woodlawn/AuldenGrange/Santry Court, Castletimon, Kilbarron, Cromcastle, Ballyshannon Rd. and Lorcan. How current facilitates such as local schools, Northside Shopping Centre, a new Primary Care Centre in Kilmore (due to be developed in 2016/17) and the Astro Turf could support the development need to be considered. Gaps in services and amenities need to be identified and planned for as part of the design and planning permission process.

Amenities

I note the provision of a high quality park (s). A a public rep serving the area and living near by a key gap in amenities identified by local residents is facilitates for older kids and teens – a community centre, a basketball court, a football pitch for example. It would be imperative that space be structured for such amenities. A large landscaped park, while beautiful and attractive needs to include actual sporting and play amenities if it is to fully serve the local community, promote social cohesion and prevent the possibility of anti-social behaviour. It would be imperative that DCC reserve significant space in its ownership for community use. For example, a large mixed use unit could be reserved to serve as a community hub, similar to the hub in Clongriffin, to provide a base/community centre for local community groups of all ages to meet and organise activities for all age groups within the community. Consideration should be given to including a Family Resource Centre as part of such reserved space.

Schools

Gaelscoil Colmcille borders this site and Scoil Fhursa is within 350m. Both these schools need to be engaged with to ascertain their capacity to serve possible new students and what amenities the site might be able to offer that might enhance their current facilitates.

Height

I have reservations about the building heights outlined in the objectives – it would be imperative that the heights are scaled with two storey buildings nearest to the Castletimon and Lorcan and increased heights rising toward the M1. However, I do not think a slender 10 storey feature building in the north west corner would be visually appealing – there is no other building on the other side of the road to balance it out.

Access, Traffic and Public Transport

One of the key concerns with this development is the impact additional cars from the unit owners/tenants will have on both local roads/streets and the Oscar Traynor Rd. This road is the last slip road off the M1 and the key artery from the M1 towards Beaumont Hospital, the Malahide Rd., Artane and Clontarf areas. At peak times it is heavily congested. Further congestion will have a serious negative impact on access out of Woodlawn/Aulden Grange/Santry Court and into Gaelscoil Cholmcille at eak morning times and also.

Currently Dundaniel Rd. is also heavily congested at peak morning and afternoon times. This road cannot take any more traffic without causing major disruption to residents’ access in and out of their own driveways. Careful planning will be required to avoid Lorcan and Castletimon being used as peak time rat runs to off set congestion in other areas.

Enhanced public transport, cycleways and the extension of Dublin Bikes need to be planned for and realised in tandem with the development so as to provide alternatives to the use of cars – for example there is no public transport link between this site and the Northside Shopping Centre or the Omni Centre which are the two nearest retail areas.

Possible hotel

Given the proximity of several other hotels I question the inclusion of a hotel. Perhaps it would be viable if it were to offer additional facilities such as a pool, gym, spa, bistro and bar to local residents.

Communication and Engagement

It is imperative going forward that the local community are actively consulted and engaged with in the development of the site.

Filed under Uncategorized